An Excerpt From Bruised and Wounded by Ronald Rolheiser

Some years ago, some other friends of mine lost a daughter to suicide. She was in her early twenties and had a history of clinical depression. An initial attempt at suicide failed. The family then rushed round her, brought her to the best doctors and psychiatrists, and generally tried in every way to love and coax her out of her depression. Nothing worked. Eventually she died by suicide. Looking at their efforts and the incapacity of their love to break through and save her life, we see how helpless human love can be at a point. Sometimes all our best efforts, patience, and affection can’t break through to a frightened, depressed person. In spite of everything, that person remains locked inside of herself, huddled in fear, inaccessible, bent upon self-destruction. All love, it seems, is powerless to penetrate.

Fortunately, we are not without hope. The redeeming love of God can do what we can’t. God’s love is not stymied in the same way as is ours. Unlike our own, it can go through locked doors and enter closed, frightened, bruised, lonely places and breathe out peace, freedom, and new life there. Our belief in this is expressed in one of the articles of the creed: He descended into hell.

Fortunately, we are not without hope. The redeeming love of God can do what we can’t. God’s love is not stymied in the same way as is ours. Unlike our own, it can go through locked doors and enter closed, frightened, bruised, lonely places and breathe out peace, freedom, and new life there. Our belief in this is expressed in one of the articles of the creed: He descended into hell.

What is meant by that? God descended into hell? Generally, we take this to mean that, between his death and resurrection, Jesus descended into some kind of hell or limbo wherein lived the souls of all the good persons who had died since the time of Adam. Once there, Jesus took them all with him to heaven. More recently, some theologians have taken this article of faith to mean that, in his death, Jesus experienced alienation from his Father and thus experienced in some real sense the pain of hell. There is merit to these interpretations, but this doctrine also means something more. To say that Christ descended into hell is to, first and foremost, say something about God’s love for us and how that love will go to any length, descend to any depth, and go through any barrier in order to embrace a wounded, huddled, frightened, and bruised soul. By dying as he did, Jesus showed that he loves us in such a way that his love can penetrate even our private hells, going right through the barriers of hurt, anger, fear, and hopelessness.

READ: Into Safe Hands: A Meditation On Dying for Advent and Christmas by Ronald Rolheiser

We see this expressed in an image in John’s Gospel where, twice, Jesus goes right through locked doors, stands in the middle of a huddled circle of fear, and breathes out peace. That image of Jesus going through locked doors is surely the most consoling thought within the entire Christian faith (and is unrivalled in any other world religion). Simply put, it means that God can help us even when we can’t help ourselves. God can empower us even when we are too hurt, frightened, sick, and weak to even, minimally, help ourselves.

I remember a haunting, holy picture that I was given as a child. It showed a man, huddled in depression, in a dark room, behind a closed door. Outside stood Jesus, with a lantern, knocking softly on the door. The door only had a knob on its inside. Everything about the picture said: “Only you can open that door.” Ultimately what is said in that picture is untrue. Christ doesn’t need a doorknob. He can, and does, enter through locked doors. He can enter a heart that is locked up in fear and wound. What the picture says is true about human love. It can only knock and remain outside when it meets a heart that is huddled in fear and loneliness.

But that is not the case with God’s love, as John 20 and our doctrine about the descent into hell make clear. God’s love can, and does, descend into hell. It does not require that a wounded, emotionally-paralyzed person first finds the strength to open herself to love. There is no private hell, no depression, no sickness, no fear, and even no bitterness so deep or so enclosed that God’s love cannot descend into it. There are no locked doors through which Christ cannot go.

But that is not the case with God’s love, as John 20 and our doctrine about the descent into hell make clear. God’s love can, and does, descend into hell. It does not require that a wounded, emotionally-paralyzed person first finds the strength to open herself to love. There is no private hell, no depression, no sickness, no fear, and even no bitterness so deep or so enclosed that God’s love cannot descend into it. There are no locked doors through which Christ cannot go.

I am sure that when that young woman, whose suicide I mentioned earlier, awoke on the other side, Jesus stood inside of her huddled fear and spoke to her, softly and gently, those same words he spoke to his disciples on that first Easter day when he went through the locked doors behind which they were huddled and said: “Peace be with you! Again, I say it, Peace be with you!”

This Child of Faith: Raising a Spiritual Child in a Secular World

This Child of Faith: Raising a Spiritual Child in a Secular World

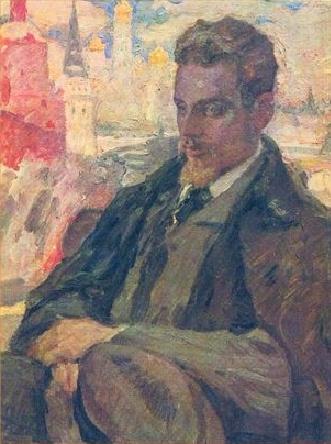

Rilke has become, for me, one of the trustworthy guides into what the late Gerald May simply called “the Slowing,” a theme that is at the heart of Advent. For we need to slow down to savor what this season is about, opening ourselves to the lure of its mystery. In one of Rilke’s letters, he suggests what this might entail in our lives: “To let every impression and every seed of a feeling realize itself on its own, in the dark, in the unconveyable, the unconscious, beyond the reach of your understanding, and to await with deep humility and patience the hour when a new clarity is born: this alone is to live artistically, in understanding as in creation.” This is what we are made for, as the themes of Advent remind us.

Rilke has become, for me, one of the trustworthy guides into what the late Gerald May simply called “the Slowing,” a theme that is at the heart of Advent. For we need to slow down to savor what this season is about, opening ourselves to the lure of its mystery. In one of Rilke’s letters, he suggests what this might entail in our lives: “To let every impression and every seed of a feeling realize itself on its own, in the dark, in the unconveyable, the unconscious, beyond the reach of your understanding, and to await with deep humility and patience the hour when a new clarity is born: this alone is to live artistically, in understanding as in creation.” This is what we are made for, as the themes of Advent remind us.