Chapter 1

Hazel Valley

Prospect, Pennsylvania

May 1, 1952

5:53 am

When Jess Hazel left the warmth of the house that morning of the Light and trudged down the hill to the barn, he did it with unusual reluctance. He was in a dark mood, tired to the bone after another long night of poor sleep. The conversation between his parents, low and tense and punctuated by his mother’s sobs, had gone so late it was early by the time it ended. How early, he did not know. If he had risen to check the time, Clyde and Millie would have known he was lying awake in the room above theirs, every nerve stretched tight. What he did know was that by 5:30, when he’d left his bed unrested, all sound had ceased. And he knew that down in the kitchen, the percolator, which should have been working at a pot of coffee strong enough to get him through chores, was as cold and silent as the house. Seeing it, he had crept back upstairs to finish dressing in the dark, cursing the bed across from his own. Cursing the absence of his only brother in it.

The Fourth of July would mark a year since Walter had up and joined the Marines, got himself shipped off to Parris Island for basic training and from there to Korea, to help solve that peck of trouble. Jess missed him with the pain of a phantom limb. Two years and three months between them, but he and Walter were as close as twins. So close, they were, in fact, that Jess sometimes pondered, as he was inclined to do all life’s hidden things, the strength of their bond. A pure gift, he would most often decide, after considering awhile. What else could it be, when they were as different as dawn from dusk and hardly looked like kin?

He and Walter resembled one another so little, in fact, that at the drunken send-off shindig Walter’s friends had thrown—a bonfire gathering of folks who (if you didn’t count Mike and Sully Latona) were all strangers to Jess—not one person had taken them for brothers. Likeable, easygoing Walter had the dark Cherokee eyes and the small, light frame of their mother’s folks. Jess was six feet and seven inches, taller than any man in the valley, even their father. And as if the curse of absurd height had not already marked him as the peculiar son, nature had also given Jess a wiry bramble of hair, black as a crow’s wing, and sunken eyes of the palest gray. “Hungry,” a canny old woman selling lemonade at the county fair had once said of his eyes, “like a young Lincoln,” after which he had started casting them mostly downward.

He made his way around the barn to the milking shed behind, mud sucking at his boots. Storms in the south had brought to the valley warm winds and an early thaw. He thought of climbing up to the loft and knocking back in the hay as Walter used to do, he was that weary. But it would never work and he knew it. When Walter had slept in the loft, Jess had always been tending to the herd. Left to wait, the cows would complain in voices loud enough to bring an irritated Clyde. Also, it was Thursday. Pat Badger would be pulling down the lane soon, wanting milk for the weekend. Not the sort of man you asked to stand by and watch you dig sleep out of your eyes.

Sage. That was how Jess’s mother, Millie, described Pat. A single word, spoken as though she held an egg on her tongue, was somehow always closer to the point than Jess could get working with full sentences. Pat did take a keener, wider, more generous view of the world than most anyone else Jess knew. In fact, on another morning when Jess wasn’t so cross, he might have sought counsel, asked the sage old farrier to see what he couldn’t, which was how a fellow was supposed to live with any pleasure now that Walter wasn’t going to come sliding into the milking shed of an evening, late as the dickens and cheerfully unrepentant. No working wisdom out of Pat today, though. Jess had no patience for it. The man had to be tapped like a great old tree, and the sap ran very slow.

The horses had heard him coming down the hill. Big Jake thumped on the stall door with his hoof and Maggie called out, shrill and insistent, demanding Jess stop by the tack room and dip his hand into the potbellied jar on the shelf. He ignored the pair. They knew full well Millie’s ginger snaps were only given out in exchange for work. Some days they begged for them anyway. He ducked to miss the doorframe as he entered the milking shed and slipped quietly inside. The bawling of the cows only made him more eager for the peace the work of milking would bring. He set down the sanitizing buckets and began filling the troughs with fodder. When all was in readiness, he opened the lower door, letting in the noisy, complaining herd. The boss cow entered first. He greeted her as he always did, with a gentle slap on the rump. As she passed, he gazed over the bony crests of her hips to the valley stretched long and slender below the barn. Where the thin light caught the dew, the grass sparkled and glinted, as if the pasture had a sugar glaze.

So often at this hour, when the sun still hid behind the wall of Kerry Mountain, when the valley lay wrapped in the pale gray shadows of earliest dawn, Jess felt the thrill of a watcher, stealing in to witness a hidden, mystic rite. It pleased him to think that however old and practiced the ritual was now, it hadn’t always been. A gawky young first night had once had to learn this graceful way of making an exit, of taking proper leave of the world, smoothly handing it off to the day.

It was just as this rite was ending that the light appeared.

Read More (just $1.99 on Amazon.)

—

Also! This week for just $1.99 on Amazon!

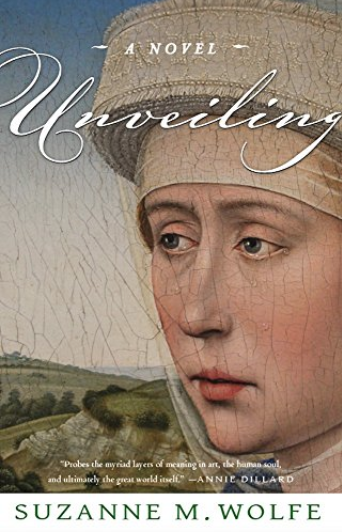

Unveiling: A Novel by Suzanne M. Wolfe

Rachel Piers, a brilliant young conservatrice at a Manhattan art gallery, is given the dream assignment of restoring a mysterious medieval painting in a church in Rome. She seizes the opportunity to advance her career in one of the most inspiring and romantic cities in the world, leaves behind a bitter divorce and painful childhood incident. As Rachel meticulously restores the damaged artwork, she uncovers layers of her soul that she would rather be kept hidden. Written in descriptively sumptuous prose, Unveiling brings the ancient city of Rome vividly to life and reveals a courageous woman coming to terms with a tragic past.

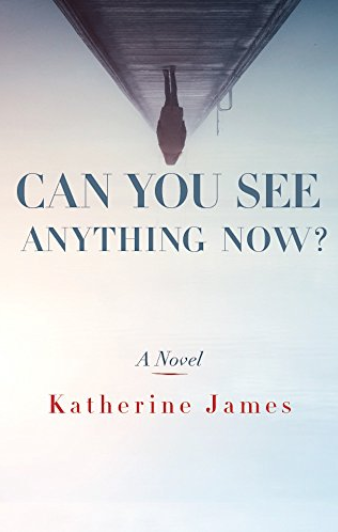

Can You See Anything Now? by Katherine James

A debut Novel that follows a year in the small town of Trinity where the tragedy and humility of a few reveal the reality of people’s motivations and desires.

This is a story without veneer, and for readers who prefer reality to sanitized fiction—this book is unsentimental, and yet grace-filled.