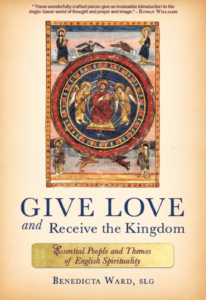

From the greatest living expert on the history of English spirituality comes the most expansive collection of her work ever published. Benedicta Ward’s Give Love and Receive the Kingdom is designed to both inspire and educate. Read the Introduction, and prepare to be inspired.

—

These papers were all written for different times and occasions, and I am grateful to the editors at Paraclete Press and SLG Press for the suggestion of reprinting them under one cover. Reading them together is for me like looking through windows of different coloured glass at many people, times, and places; my task is that of a window-cleaner, making it possible for others both to see through clearly and pass over to find pasture, as I do among such friends. The message of these writers is certainly not one of ease and comfortableness, but of faith, hope, and love. Only after wrestling with God, like Jacob in the dark, and being like him permanently wounded, can anyone go towards the brother one has hated and say, “I see your face as the face of God” (Gen. 33:10). They all used their own life experience, starting where they were, to express the impact on them of the Gospel through self-knowledge and God-knowledge, by submission and repentance, coming closer always to the reality of God in Christ. They spoke out of lives lived within and on behalf of a world as torn and agonizing and filled with doubt as our own.

There are many written sources to draw upon in understanding the inner life of our predecessors in these islands. They were human beings like ourselves, and in exploring their journeys we can be refreshed and encouraged in our own. A search for their backgrounds could begin with the records of the evangelisation of the sixth-century Germanic settlers in Britain who came from different places: there were the existing British Christians, the missionaries sent by Gregory I from Rome, and contacts with Christian Gaul, as well as missionaries and preachers from Ireland and Iona. In effect, the message they brought came originally from Rome, coloured by the different ethos of each group, and they intermingled freely, creating eventually a homogeneous Christian nation out of disparate tribes and peoples.

The chief sources for knowing about them at this early stage are the works of the Venerable Bede (635–736), the greatest scholar of his age and the only Englishman to have been accorded the title of Doctor of the Church. He made it his life’s work to offer the new Christians the traditions of Mediterranean Christianity, linking them with the world of the New Testament and the Fathers of the Church, not just as a part of the past, but as life here and now for a new and living people of God.

The basis of Anglo-Saxon spirituality was thus formed by love and not by force. Augustine began by praying and fasting in a small church with the queen and her court, establishing a lasting link between church and state which was dependent on unity of prayer and reality of conduct. This link is seen clearly in the conclusion of the Synod of Whitby where a major division was healed not by reasoned argument or political force but by trust in the resurrection: “King Oswiu said, ‘Since Peter is the doorkeeper I will not contradict him, lest when I come to the gates of heaven there may be no-one to open them.’”1

In a rough world, existing ways of life were not so much destroyed as transformed: a love of the glory of gold became a love for the beauty of holiness. Awareness of the terrors of both nature and super nature around them, as well as of sin within, led to a strong emphasis on penance, personal as well as corporate, which coloured devotion and affirmed the centrality of the Cross and the Last Judgement. Love of a lord was transferred to love of the high King of Heaven, and love of kin could be the basis of care for members of the Church. This instinctive need for companionship was transferred also to the saints, who were known as always present and always available in prayers, miracles, and visions.

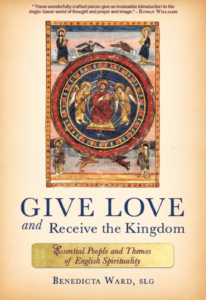

Bede preserved for us details of this lived Christianity in stories which show the ideals which inspired the new Christians. This was done orally by preaching but also by using the new technology of writing. Augustine had brought with him to a non-literate society a silver cross and an icon of Christ, but also a book which would change the ways of communication forever. He offered these to King Ethelbert and his thanes as tokens of “a new and better kingdom.”2 His approach was in line with the policies of Pope Gregory the Great who sent him, in that he was prepared to build on the existing ideals and customs of the English and transfigure rather than destroy. A serious, practical, and lasting spirituality was the result, based on the Scriptures and the liturgy of the Church, which is illustrated by the cover of this book, which shows the picture of Christ in majesty. It is taken from the Codex Amiatinus, the oldest copy of the Latin Vulgate, which was made at Wearmouth Jarrow in Bede’s time, thus presenting the Bible as the main window into the light which shone through the lives of our friends.

The sense of living in the ante-chamber of heaven, with the shadow of judgement as well as the promise of mercy always present, coloured all aspects of later medieval devotion, but the eleventh century saw a turning point towards a more personal interior approach. The key figure in this was the theologian-monk Anselm of Bec, who ended his life as archbishop of Canterbury (1033–1109). He made a break with the long tradition of prayer which flowed mainly through the channels of the psalms by creating out of them a new kind of poetic material for the use of anyone who wanted to pray. His Prayers and Meditations arose out of his own private prayer, and he sent copies of them to those of his friends who asked for them, together with simple and practical advice about how they could be used. Naturally his prayers were shaped by his monastic background and interests, but from the first they were popular with men and women living a busy Christian life in society for whom the monastic life of prayer was an ideal with which they longed to be associated. Anselm’s secretary and biographer, Eadmer, wrote of these prayers:

With what fear, with what hope and love he addressed himself to God and his saints and taught others to do the same. If the reader will only study them reverently, I hope that his heart will be touched and that he will feel the benefit of them and rejoice in them and for them.

Anselm saw no rift between Christian thought and Christian devotion. As well as being a good pastor, a man of prayer, and an affectionate friend, Anselm was an outstanding scholar, with one of the keenest minds of all time, and he applied his intellect to the lifelong task of thinking about and living for God. Every part of his fine mental equipment was stretched to its limit, seeking and desiring God in practise as well as in thought. At the end of the Proslogion he wrote:

My God,

I pray that I may so know you and love you

that I may rejoice in you

and if I may not do so fully in this life,

let me go steadily on

to the day when I come to that fullness.

It is clear from this quotation, which comes from the last part of his most brilliant philosophical work in which he first proposed what was later called “the ontological argument” for the existence of God, that Anselm knew very well that God is not known by the intellect on its own but by the heart and mind together. His own discovery about prayer was what he passed on to others as “faith seeking understanding.” In his advice about praying, he insisted that the first necessity was to want to pray and be ready to give up some part at least of concern with oneself in order to be “free a while for God.” In a quiet place, alone, Anselm offered the person praying words that he himself had prayed, arising out of, but not confined to, the Scriptures used in personal and intimate dialogue with Jesus.

It is possible to find the same approach in Julian of Norwich (1342– 1413.) Julian composed two books, one a long version of the other, called Revelations of Divine Love, expressing the flowering of English prose as well as containing the first sustained theology to be written in English. She lived as an anchoress in a cell built onto the wall of the church of St. Julian in Norwich. In the twentieth century, she became well known and indeed popular, but she was very little known in her own times and all but lost sight of at the Reformation. Her works were recovered and edited only at the end of the nineteenth century, as if they had been preserved especially for our times. Her theology was based on a background of immense global suffering and despair. The time and opportunity for a peaceful life was challenged in the most basic manner possible by universal attacks of a fatal plague, called the Black Death, which struck at everyone and recurred; it was almost impossible to assuage.

There are so many deeds which in our eyes are evilly done and

lead to such great harms that it seems impossible to us that any

good result should ever come from them.5

She was well aware of the sinful state of all: “I saw and understood that we may not in this life keep us from sin as completely as we shall in heaven.” But she was sure that here and now we should not despair: “Neither on the one hand should we fall low in despair, nor on the other be over reckless as if we did not care but we should simply acknowledge that we may not stand for the twinkling of an eye except by the grace of God and we should reverently cleave to God in him only trusting.”

With this dark background of fatal illness and continuous warfare the poet Langland (1332–1400) presented a vision of realistic but loving hope similar to that encountered in Julian:

I dreamt a marvellous dream;

I was in a wilderness I could not tell where . . .

and between the tower and the gulf

I saw a smooth field full of folk,

high and low together. (Piers Plowman)

The tower of truth and the gulf of sorrow: and between them a field full of folk. This vision is concerned with the folk between these two extremes, and in some ways, it is a true vision of Christian life in any time or place. There is always a dynamic unity between the content of a faith (the “tower of truth”) and the way it is lived out (“the gulf of sorrow”) not by a special elite but by the “folk” themselves. Spirituality cannot be seen as a pure intellectual stream of consciousness flowing from age to age among articulate people only; it is always the lens of the gospel placed over each age, each place, each person.

This unity of understanding within the changing settings of the disasters and challenges of life can be seen in Bede, Cuthbert, and Anselm. Alongside them are the hermits of the twelfth century, and the fourteenth-century writers Julian of Norwich and Langland. Andrewes, Taylor, and Frank in the seventeenth century show how the same approach to inner pilgrimage continued in changing social contexts, a stream of ever-moving pilgrims going towards the life of heaven.

We are all engaged in this pilgrimage with them, and there is refreshment in such companionship. We are all Bunyan’s Christian, and as well as being his Mr. Despair, we are also his Faithful-unto-Death. We with him will cross over in the loving company of friends, where for us as for him “all the trumpets sounded for him on the other side.” Between the tower of truth and the gulf of sorrow our predecessors stood, as we do, within a field full of folk with only one rule: “Give love and receive the kingdom!”

Benedicta Ward, Oxford, 2018