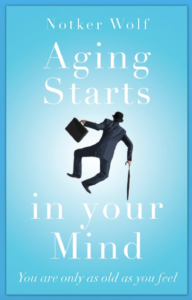

In this excerpt from Aging Starts in Your Mind: You’re Only As Old As You Feel Chapter 3, author Notker Wolf, shares how rock and baroque music do go together after all. http://bit.ly/2LLxkYi

—

Chapter 3: Greetings from Pink Floyd

This summer I had a two-week holiday in a monastery on Lake Wolfgang. (My annual leave is usually shorter and sometimes canceled altogether.) While I was there, I received an invitation to the Tollwood Festival in Munich, and I must admit I didn’t know exactly what it would be like: a kind of Woodstock but lasting for weeks and without the mud? It didn’t matter, the offer to perform with my band in the Andechser tent was appealing.

Well, I said to myself, if Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger, and others from the glorious age of rock music, with their lined faces, still dare to perform, you can do it too—in any case they won’t have to get you off any drugs first. I accepted the invitation.

Someone drove me from Austria to Munich. “Oh yes, you’re the father from the mountain,” said the security guard at the entrance to the Tollwood grounds with a glance into our car. Apparently, he’d seen the television interview I did on the summit of the Dürrnbachhorn with Werner Schmidbauer. “Tell you what, I’ll let you through here, then you won’t have so far to walk to the tent.”

I already felt at home, even though I’d never been here before. The guard signaled his colleagues, so the way was open all the way to the Andechser tent, and after a short sound check (the other band members had arrived earlier) we were ready for our concert, two hours of rock music in the tent from 7:30 to 9:30. Although I have to admit I sometimes left the stage. A concert that long is too much for me these days, plus I don’t have the time to rehearse enough songs to fill an evening program. I’m lucky if I find two or three hours at Sant’Anselmo a few days before our performance to put on our CD and rehearse my parts on guitar flute. So I played in two of the four sets, and my band did the rest on their own.

Apart from the singer, our band always has the same members it did in the good old days when I was Archabbot of St. Ottilien and the others were students at our school. That’s a long time ago now; my fellow musicians have also grown older, but unlike me, they aren’t aware of it yet.

And it’s still tremendous fun for everyone. For example, we did a performance under the southern sky in front of a large audience at an arena in Pescara, Italy, dubbed “Pink Floyd Sends Greetings from Pompeii,” that was unforgettable. As was as our show soon afterward in Seeon, a magnificent monastery on a lake island in Bavaria. Seeon has made a name for itself as an event location, and I was invited to give a lecture there to the managers of the Ingolstadt hospital. “Bring your band along,” they said. After the talk at dinner in the magnificent, colorful refectory, I still had my doubts about playing in this setting, wondering if rock and Baroque really went together. But a little later the set got going and I enjoyed playing as usual, and the experience was a real miracle.

That’s what the head of trauma called it anyway—it was absolutely unbelievable how all differences disappeared immediately, all formalities forgotten, all inhibitions gone. Everyone danced until they were ready to drop: consultants, lawyers, administrative staff, the whole management team, men and women, all mixed up together. Rock and baroque do go together after all.

This was followed the next evening with a performance in Carinthia, Austria, inside the venerable walls of St. Paul, where on the following morning I would be saying the celebratory Mass and preaching, before flying back to Rome in the evening.

–

Let’s catch our breath. I know the whispers that are going around. From one direction I hear the heavy sigh, “He’ll never fit in with the rest of us.” From another the warning, “Be careful, you’re the abbot primate, please behave accordingly.” And then there are my primary school classmates, who to this very day visit me in Rome from time to time and exclaim with amazement, “Werner, [my birth name] you haven’t changed a bit!” What can I say?

Yes, it’s probably true—no one who’s known me for a long time will notice any big difference today. I’ve never been antisocial; my constant activity isn’t a gift of old age. And, while it’s true I’m the abbot primate, the expression “befitting one’s social status” has never meant anything to me.

How I go about my work, how I define my role and how I shape it, is my decision, and anything that could possibly qualify as “unseemly” I clarify with the Lord Jesus Christ: he’s my model.

Of course I’m going to make mistakes, but I don’t lose sleep over it because I know nobody’s perfect, and I don’t need to be either. Christ himself appointed the far-from-perfect Peter as the leader of his followers, a person who even disowned him when it came to the crunch. So we can go wrong, but we shouldn’t let ourselves be influenced by the worriers. I’m reminded of a grave inscription in the Campo Verano, a cemetery in northern Rome, which says, Non flectar, “I will not bend.”

“Slow down a bit,” some say; “Please tone it down,” say others. And I say, “Come with me.” Come, for example, to Altenburg Abbey close to Vienna for the interreligious song event. The first benefit concert was held there in 2012 to restore the nearby Jewish cemetery that was devastated in 1938. The abbot of Altenburg had urgently asked me to participate. “We need you, and don’t forget your flute!” Oh no, another appointment. But miraculously I found a gap in my schedule, and I traveled there without knowing what awaited me.

With four hundred visitors, every seat in the monastery’s library was filled. I was in good company. The singer was the chief rabbi of Vienna, a man with a sense of humor and a powerful voice; another rabbi played the keyboard, the Protestant bishop of Vienna was drummer, and a gentleman from the local finance ministry was saxophonist—completing the spectrum, as he had left the church.

Behind us was the boys choir of Altenburg, and we gave it all we’d got, playing Yiddish songs and gospel songs, and receiving enthusiastic applause at the end of every number. Afterward, when everyone was standing around in the richly decorated, brightly lit library, still suffused with the music, a high-ranking politician from Lower Austria came up to me and said, “You know, Abbot Primate, our church in Austria is at such a low ebb. If it wasn’t for you Benedictines. . . . You’re the enlivening element.”

The enlivening element? I am grateful to hear that. It’s exactly what I want to be. It’s exactly what I wish for my order as a whole—to have a stimulating effect on society, in all the places in the world where we’re represented: this is one of the three great visions that guides me.

To achieve this goal we must of course be alive ourselves, and this requires abandoning well-worn tracks. I can’t determine the pace of the world, I have no influence on the great upheavals of the time, but we mustn’t isolate ourselves from these changes, and lose contact with the world, with life, with other people. After all, what are we here for? For the world, life, and other people.

I think my continuous connection with the world of rock music has had very positive consequences. First of course, for myself, because I love rock music, and after all these years it still epitomizes vitality and zest for life. Second, however, because I reach many people through this music.

For example, in Barcelona, where I was to give a lecture to the executives of an international corporation. In the introductory session the moderator told them about our band’s performance supporting the legendary Deep Purple, and when they didn’t quite believe him he referred to the YouTube entry “Deep Purple mit Abtprimas Notker Wolf—Smoke on the Water.” (Yes, we played the song together.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZjJI8zBG0yQ

As if on cue all the participants took out their smartphones and were too busy tapping and swiping away to listen to my words of welcome, but with this I had won them over. Abbot Primate Notker Wolf supporting Deep Purple? On stage with Ian Gillan and Steve Morse? An introduction like this greatly increases receptiveness. It breaks with convention, makes it easier to talk to people, and spares me the usual small talk.

Sometimes the rock music even merges informally with the Christian message. During our Tollwood performance in the Andechser tent a banner with the words “Highway to Heaven” hung above the stage, a combination of the AC/DC title “Highway to Hell” and the Led Zeppelin classic “Stairway to Heaven”; I would never have worked it out myself, but of course it fit superbly. And many of the songs we play are original compositions and reflect our origins at the St. Ottilien mission monastery.

My favorite song is “My Best Friend,” and if you listen carefully, you’ll realize that we’re singing about Jesus Christ, the only one who doesn’t abandon you if all your other friends let you down. To play it safe, I introduce such songs myself, also so no one in the audience thinks my black Benedictine habit is just a particularly crass stage outfit.

–

Travels abroad, stage performances, meetings, conferences, lectures, interviews, TV appearances, magazine columns, books, and building projects: admittedly some things in the repertoire traditionally belong neither to the responsibilities of an abbot primate nor to the role of an almost-seventy-five-year-old.

One side effect is the challenge of managing my schedule. This involves never-ending tinkering: appointments constantly have to be changed, inserted, or added. Because of special requests and spontaneous inquiries, half of it ends up being improvisation, so no one else could possibly be expected to get their head around it? That’s why I take my schedule into my own hands.

Another side effect is amateur psychologists having reasons to whisper about me. “He needs it,” they say. “He can’t do without it. He’s determined to make a difference and leave his mark on the history of the order. He can’t stop for fear of losing his importance.” Or, “He’s running away from himself.”

It’s true that I have a duty as abbot primate. It’s also true that I see it as my greatest and finest duty to open as many doors to the future as possible for my order. That would scarcely be possible if I didn’t keep on the move, respond to contemporary trends, try out new and perhaps even unheard of things, while at the same time giving an example of the vitality I wish for my order. We’ve both reached a certain age, my order and myself—in the case of the former it’s 1,500 years. Wear and tear are not alien to us.

But that shouldn’t be a reason for either the order or me to slacken. Of course no one is irreplaceable. But as long as we live we’re needed. That is a possible answer to the questions confronting anyone in the third phase of life. We may be unimportant as individuals, but the ideas we promote, the efforts we make out of love or conscientiousness, are not.

We’re needed. And it’s wonderful to be needed. It may be quite strenuous, as in my case. But when people ask me, “How do you manage it? How can you stand it?” the answer is simple: Joy is my lifeblood—joy in my work, joy of meeting people, joy in music. Also joy in nature, the different shades of green of the oaks, pines, cypresses, and olive trees in the southern sunlight. Joy in the sea I like to sit by and swim in; joy in the warm golden tone of the evening light flooding into my study.

Today Ben reminds me of the character Asriel Dreemurr, a child, from a video game called Undertale. Both of them had a very innocent nature, and they were both very kind and friendly. And the main thing they share is that they were both killed. Recently when I was playing through Undertale, I noticed this connection between Ben and Asriel. I started to cry during Asriel’s speech at the end of the game. It was a sad speech. He died for no reason, like Ben. But I love playing Undertale anyway because I like seeing Ben and so many of my friends in the game’s characters.

Today Ben reminds me of the character Asriel Dreemurr, a child, from a video game called Undertale. Both of them had a very innocent nature, and they were both very kind and friendly. And the main thing they share is that they were both killed. Recently when I was playing through Undertale, I noticed this connection between Ben and Asriel. I started to cry during Asriel’s speech at the end of the game. It was a sad speech. He died for no reason, like Ben. But I love playing Undertale anyway because I like seeing Ben and so many of my friends in the game’s characters. And God is always there for me, and I know that he always will be there for me. Whenever I am feeling worried about myself, my family, or any of my friends, praying to God is always helpful because I can always ask him to watch over the person I am praying about. I can always trust God to watch over my friends and family because I know he will always find a way to make things better.

And God is always there for me, and I know that he always will be there for me. Whenever I am feeling worried about myself, my family, or any of my friends, praying to God is always helpful because I can always ask him to watch over the person I am praying about. I can always trust God to watch over my friends and family because I know he will always find a way to make things better.

Jean Vanier was awarded the Templeton Prize in 2015. He is a philosopher, theologian, and man of letters with great heart and compassion. The first L’Arche Community was started in 1964 in Trosly-Breuil, a village in the north of Paris, when Vanier invited two people with intellectual disabilities to live with him in a small house. Today, L’Arche is made up of 151 communities spread over five continents.

Jean Vanier was awarded the Templeton Prize in 2015. He is a philosopher, theologian, and man of letters with great heart and compassion. The first L’Arche Community was started in 1964 in Trosly-Breuil, a village in the north of Paris, when Vanier invited two people with intellectual disabilities to live with him in a small house. Today, L’Arche is made up of 151 communities spread over five continents.

Laurie M. Brock, a former attorney, is an Episcopal priest serving St. Michael the Archangel in Lexington, Kentucky. She volunteers as a crisis chaplain with the Lexington Police Department, blogs at revlauriebrock.com, and frequently leads retreats for ecumenical and interfaith gatherings.

Laurie M. Brock, a former attorney, is an Episcopal priest serving St. Michael the Archangel in Lexington, Kentucky. She volunteers as a crisis chaplain with the Lexington Police Department, blogs at revlauriebrock.com, and frequently leads retreats for ecumenical and interfaith gatherings.

But that is not the case with God’s love, as John 20 and our doctrine about the descent into hell make clear. God’s love can, and does, descend into hell. It does not require that a wounded, emotionally-paralyzed person first finds the strength to open herself to love. There is no private hell, no depression, no sickness, no fear, and even no bitterness so deep or so enclosed that God’s love cannot descend into it. There are no locked doors through which Christ cannot go.

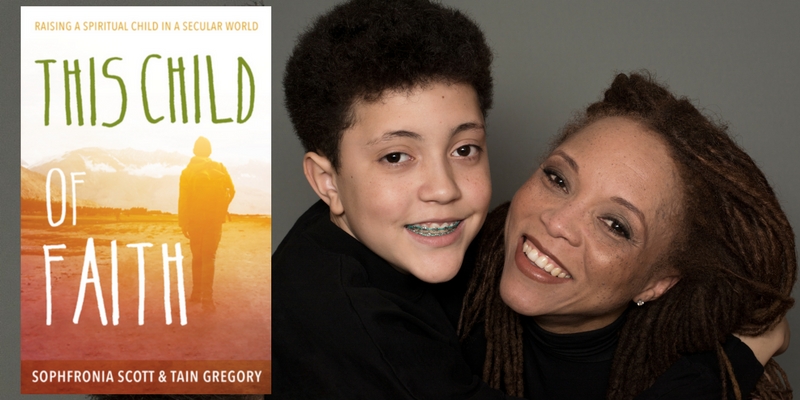

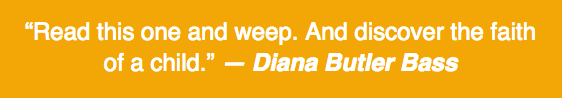

But that is not the case with God’s love, as John 20 and our doctrine about the descent into hell make clear. God’s love can, and does, descend into hell. It does not require that a wounded, emotionally-paralyzed person first finds the strength to open herself to love. There is no private hell, no depression, no sickness, no fear, and even no bitterness so deep or so enclosed that God’s love cannot descend into it. There are no locked doors through which Christ cannot go. This Child of Faith: Raising a Spiritual Child in a Secular World

This Child of Faith: Raising a Spiritual Child in a Secular World

Rilke has become, for me, one of the trustworthy guides into what the late Gerald May simply called “the Slowing,” a theme that is at the heart of Advent. For we need to slow down to savor what this season is about, opening ourselves to the lure of its mystery. In one of Rilke’s letters, he suggests what this might entail in our lives: “To let every impression and every seed of a feeling realize itself on its own, in the dark, in the unconveyable, the unconscious, beyond the reach of your understanding, and to await with deep humility and patience the hour when a new clarity is born: this alone is to live artistically, in understanding as in creation.” This is what we are made for, as the themes of Advent remind us.

Rilke has become, for me, one of the trustworthy guides into what the late Gerald May simply called “the Slowing,” a theme that is at the heart of Advent. For we need to slow down to savor what this season is about, opening ourselves to the lure of its mystery. In one of Rilke’s letters, he suggests what this might entail in our lives: “To let every impression and every seed of a feeling realize itself on its own, in the dark, in the unconveyable, the unconscious, beyond the reach of your understanding, and to await with deep humility and patience the hour when a new clarity is born: this alone is to live artistically, in understanding as in creation.” This is what we are made for, as the themes of Advent remind us. In this book, I hope to introduce the most important message of Advent through brief, daily meditations that explore some particular aspect of this message, together with a practice inviting you to deepen your experience of its meaning in your daily life.

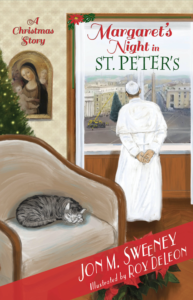

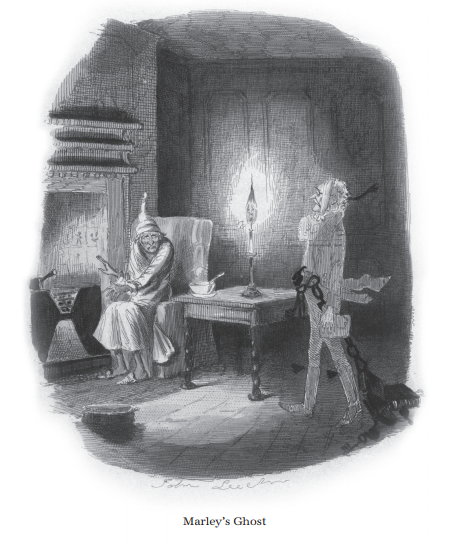

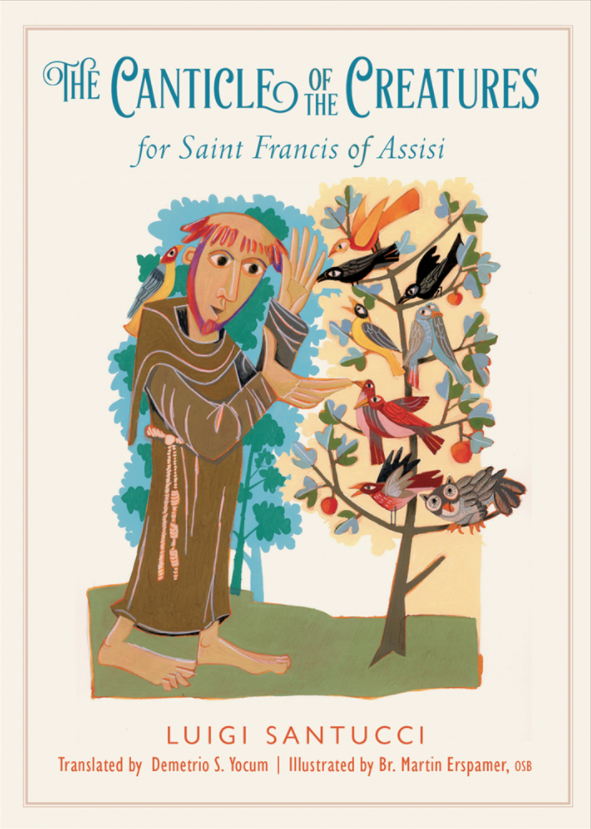

In this book, I hope to introduce the most important message of Advent through brief, daily meditations that explore some particular aspect of this message, together with a practice inviting you to deepen your experience of its meaning in your daily life. As the latest Hollywood hit, “The Man Who Invented Christmas,” opens this weekend, Paraclete Press is preparing digital and social media tie-ins for a new illustrated edition of

As the latest Hollywood hit, “The Man Who Invented Christmas,” opens this weekend, Paraclete Press is preparing digital and social media tie-ins for a new illustrated edition of

“We even imagine—and hope—that families will once again begin to read books like this aloud,” concludes Sweeney.

“We even imagine—and hope—that families will once again begin to read books like this aloud,” concludes Sweeney.

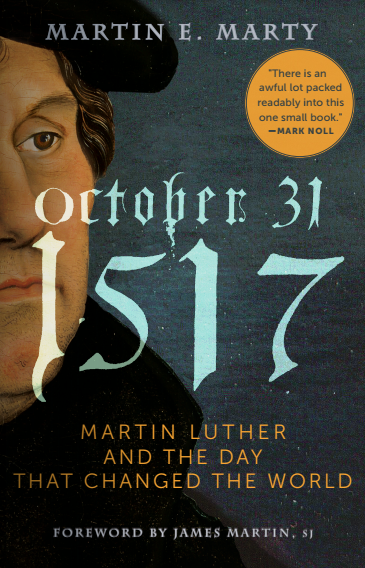

MARTIN E. MARTY is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus at the University of Chicago, where he taught for 35 years. An ordained Lutheran and historian, he has written dozens of books on Christian history and Reformation era topics, including a biography of Martin Luther. He is a National Book Award winner and was honored with the National Medal of Humanities. His passion is to demonstrate how Christianity relates to public life as well as to the personal themes of faith, hope, and love. He has participated in Christian ecumenical programs and reported on the Second Vatican Council.

MARTIN E. MARTY is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus at the University of Chicago, where he taught for 35 years. An ordained Lutheran and historian, he has written dozens of books on Christian history and Reformation era topics, including a biography of Martin Luther. He is a National Book Award winner and was honored with the National Medal of Humanities. His passion is to demonstrate how Christianity relates to public life as well as to the personal themes of faith, hope, and love. He has participated in Christian ecumenical programs and reported on the Second Vatican Council.

Ronald Rolheiser is a Catholic priest, president of The Oblate School of Theology in San Antonio, Texas, an internationally renowned speaker, and a spiritual writer whose books appeal to Christians of all backgrounds and spiritual seekers of all kinds. He is the author of many books, including the bestselling The Holy Longing, and the award-winning weekly column “In Exile,” which is carried by more than seventy newspapers worldwide.

Ronald Rolheiser is a Catholic priest, president of The Oblate School of Theology in San Antonio, Texas, an internationally renowned speaker, and a spiritual writer whose books appeal to Christians of all backgrounds and spiritual seekers of all kinds. He is the author of many books, including the bestselling The Holy Longing, and the award-winning weekly column “In Exile,” which is carried by more than seventy newspapers worldwide.

Anne, can you give us a synopsis of the book?

Anne, can you give us a synopsis of the book?

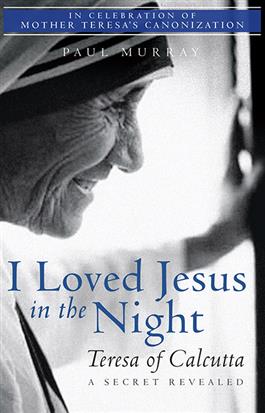

has been remarked on many times over the years by those fortunate enough to meet Mother Teresa, and that is the radiant joy which shone in her face, a joy which, from moment to moment, seemed to illumine her every expression.”

has been remarked on many times over the years by those fortunate enough to meet Mother Teresa, and that is the radiant joy which shone in her face, a joy which, from moment to moment, seemed to illumine her every expression.”

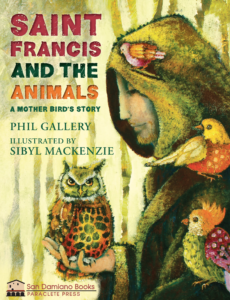

A Mother’s Love and Witness are Powerful!

A Mother’s Love and Witness are Powerful!

In Vatopaidi’s dark katholikon

In Vatopaidi’s dark katholikon