by Jack Levison

Posted on the Presbyterian Outlook, May 17, 2016

The year before men landed on the moon, I learned about the Holy Spirit in a small white church, sandwiched between a TV repair shop and a doughnut store on a busy Long Island thoroughfare. We were a church of immigrants. One day, local barber Xavier Munisteri burst out in the middle of worship in words I couldn’t understand. I figured he was speaking Italian. Turns out, he wasn’t speaking Italian — he was speaking in tongues.

The year before men landed on the moon, I learned about the Holy Spirit in a small white church, sandwiched between a TV repair shop and a doughnut store on a busy Long Island thoroughfare. We were a church of immigrants. One day, local barber Xavier Munisteri burst out in the middle of worship in words I couldn’t understand. I figured he was speaking Italian. Turns out, he wasn’t speaking Italian — he was speaking in tongues.

No one had prepared me for that moment. I hadn’t yet studied 1 Corinthians 12-14, where Paul discusses glossolalia (speaking in tongues) at length.

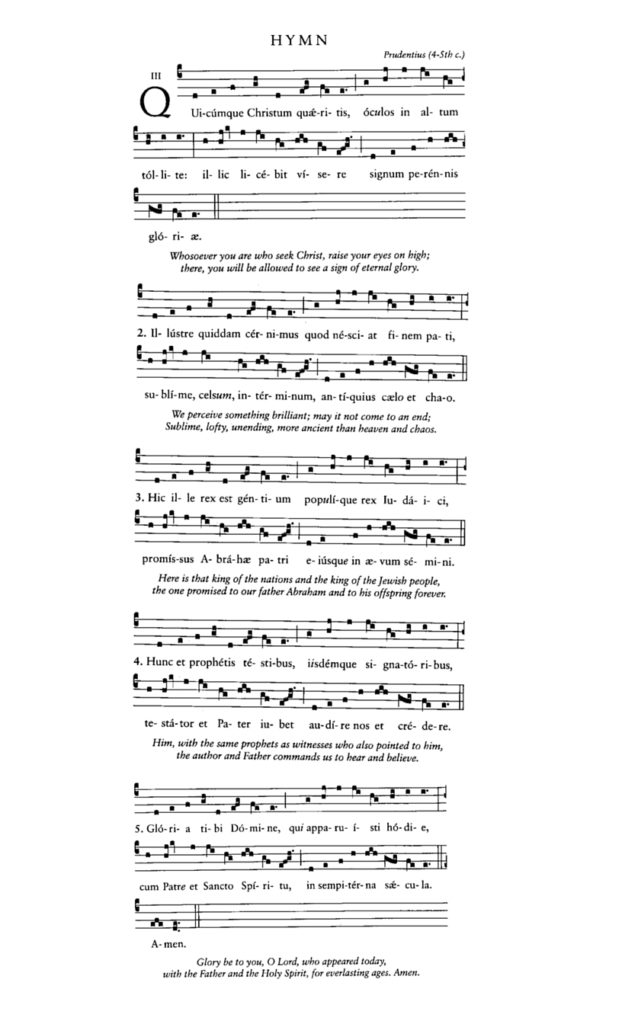

I hadn’t yet heard of the Montanists, a second century movement of enthusiasts, who championed what they called “the new prophecy,” and over whom an early Christian theologian Tertullian ran roughshod.

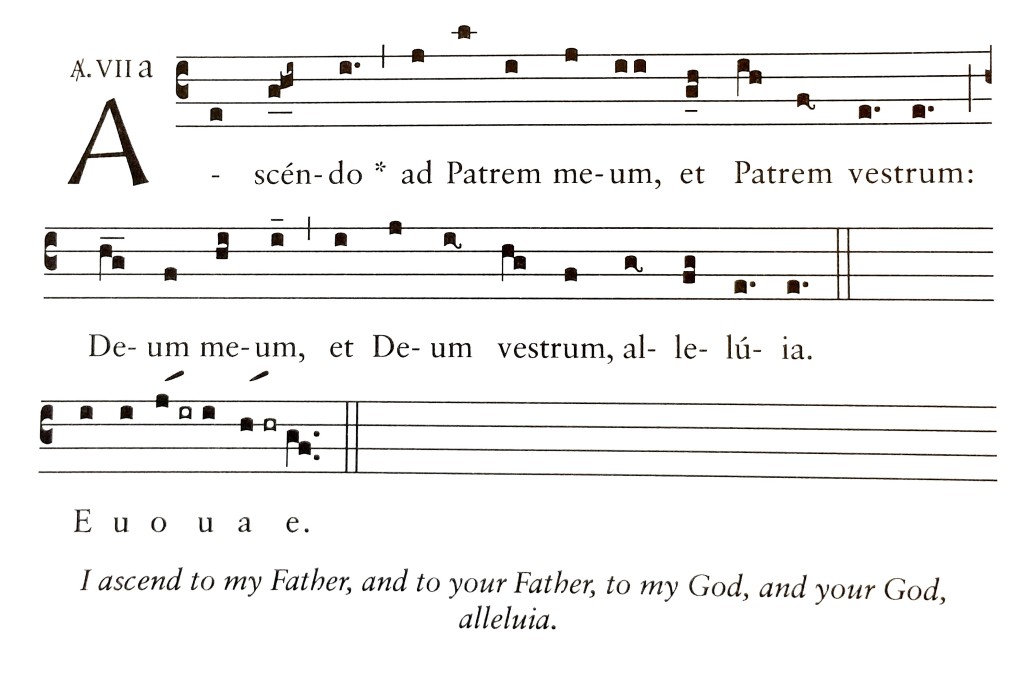

I’d never heard of the filioque, a belief that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the father and the son (and not just the father). I had no notion that in 1054, a monumental disagreement about this teaching contributed to the Great Schism between Rome and Constantinople.

I’d missed out altogether on the powerful prayer of the renowned 12-century mystic, Hildegard of Bingen:

Holy Spirit, making life alive,

Moving in all things, root of all creative being,

Cleansing the cosmos of every impurity,

Effacing guilt, anointing sounds.

You are lustrous and praiseworthy life,

You waken and re-awaken everything that is.

I didn’t even know the simple prayer, Veni Sancte Spiritus (“Come, Holy Spirit”) thought to be written by Stephen Langton, archbishop of Canterbury in the 1300s.

I certainly hadn’t been around to read the front page of the Los Angeles Daily Times from April 18, 1906, with the heading, “Weird Babel of Tongues,” followed, in italics, by New Sect of Fanatics Is Breaking Loose, Wild Scene Last Night on Azusa Street, and Gurgle of Wordless Talk by a Sister. I missed it: the birth of Pentecostalism, which has spread like wildfire throughout the world for more than a century, especially in the global South and in ever-bulging pockets of the West.

That’s right. I’d missed an entire history of the Holy Spirit. For years after Xavier burst into tongues, I knew almost nothing about the Holy Spirit. It’s surprising — astonishing, really — that a Christian should know so little about one of the persons of the Trinity. Yet others tell me that they, too, know almost nothing about the Holy Spirit.

So where do we start to encounter the Holy Spirit? With what you’ve been doing for the last minute or two while you’ve read this column: breathing.

SPIRIT AND BREATH

The Hebrew word, ruach (pronounce the ch as if you’re clearing your throat, and not as in the cha chadance), can be a breath, a breeze, a rush of wind, an angel, a demon, the heart and soul of a human being, the waxing and waning of life, a disposition like lust or jealousy (a spirit of jealousy, for instance) and the divine presence. English speakers should remember wind, breath or spirit to be like branches that grow from the thick trunk of an aged tree — ruach. At the baseline of life, ruach is breath, or better yet, spirit-breath — the pulse of life within us.

Lesson one, then, takes us to an infamous ash heap, where bone-weary Job plunks himself down on the ash heap and protests, “As long as my breath is in me and the spirit of God is in my nostrils, my lips will not speak falsehood, and my tongue will not utter deceit” (Job 27:3). Compare Job, who has little of this spirit-breath left — he talks only as long as he has spirit-breath within him — with his young companion, Elihu, who is weary, not from the stench of death, but from waiting for the old guys around him to stop talking: “For I am full of words; the spirit within me constrains me. My heart is indeed like wine that has no vent; like new wineskins, it is ready to burst” (Job 32:17-19). If Job’s spirit-breath ekes its way into the void of the ash heap in truthful words, spirit-breath (ruach) in Elihu rolls over his tongue to form angry words, long fermenting, which he supposes (wrongly, as it turns out) are full of wisdom.

It is tempting to tidy up this section on ruach as spirit-breath by urging you to meditate, to sense the breath within you, to slow down — and breathe. This would be an apt exhortation for busy believers in a buzzing era.

To end here would also be naïve, even cowardly, because a storm brews in the distance if we acknowledge the spirit-breath of God in all people. Here is the rub: Everyone, not just a Christian, receives God’s spirit-breath. The theological issue this observation raises is the relationship between the Spirit of creation and the Spirit of salvation. A horde of 20th-century theologians, such as Karl Barth, Wolfhart Pannenberg, Jürgen Moltmann and Karl Rahner, has addressed this issue. For instance, in “The Spirit of Life,” Moltmann notes:

In both Protestant and Catholic theology and devotion, there is a tendency to view the Holy Spirit solely as the Spirit of Redemption. Its place is in the church, and it gives men and women the assurance of the eternal blessedness of their souls. This redemptive Spirit is cut off both from bodily life and from the life of nature. It makes people turn away from “this world” and hope for a better world beyond. They then seek and experience in the Spirit of Christ a power that is different from the divine energy of life, which according to the Old Testament ideas interpenetrates all the living.

The bottom line is that belief in the presence of the life-giving Spirit of creation in all people is biblical if we take the Hebrew Scriptures seriously. To acknowledge the presence of God’s spirit-breath in all people does not do away with the need for the resplendent Spirit of salvation, which is poured into our hearts (Romans 5:5) so that we can love God fully, but it does complicate the matter when we peer over the cusp of church borders and acknowledge the presence of God’s spirit-breath in the lives of men and women who practice virtue and faith without naming the name of Jesus.

ONE AND MANY

Lesson two takes us to a valley of dry bones, to Ezekiel’s vision, where Spirit, wind and breath — all the same Hebrew word, ruach — enter bleached bones, causing them to clink and clank into a fresh community, raised to new life (Ezekiel 37:1-14). The Spirit here is communal, not individual.

Now fast forward 500 years, and travel to another desert, with a small settlement — not much larger than a football field — that left behind the Dead Sea Scrolls. The community at Qumran described itself as a “house of truth in Israel,” a “holy of holies for Aaron” and a “precious cornerstone.” They existed, they believed, because they possessed “the holy spirit of the community.” What’s profound about these ancient Jewish snippets? The Spirit is communal, just like in Ezekiel’s vision of dry bones come to life. The Spirit exists in community — a spiritual temple — in a way that transcends individual believers.

The apostle Paul, too, pictured the church as a Spirit-filled temple, when he railed against schisms at Corinth. His language is measured, his logic calculated:

Do you not know

that you are God’s temple and

that God’s Spirit dwells in you?

If anyone destroys God’s temple, God will destroy that person.

For God’s temple is holy,

and you are that temple (1 Corinthians 3:16-17).

Note the legal form, “If anyone destroys God’s temple, God will destroy that person,” which looks like Old Testament laws: “If someone leaves a pit open … and an ox or a donkey falls into it, the owner of the pit shall make restitution” (Exodus 21:33-34a). The Corinthians have dug a pit of schism, into which they’ve fallen, and they will pay the penalty. Cliques at Corinth are not casual but criminal.

Paul urges the Corinthians, therefore, to understand that creating spiritual provinces (we call them denominations), with one sanctified subdivision reckoned superior to the others, tears the church into shreds. For Paul, a parcelling of the Spirit is an utterly inconceivable state of affairs.

Paul returns to this point later when he pictures the church, not as a living temple, but as a body with all sorts of different parts. He bookends a list of spiritual gifts with affirmations about the Holy Spirit:

“Now there are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit” (12:4).

“For in the one Spirit we were all baptized into one body — Jews or Greeks, slaves or free — and we were all made to drink of one Spirit” (12:13).

At the heart of the Spirit’s presence in the church lies this realization: unity is not homogeneity. People of different ethnicities and different social classes, as well as differently gifted people in the church, drink of one Spirit.

Drinking the Spirit. Odd idea — yet the point is clear. If there is a sign of the Spirit, it is unity-through-diversity. There is no challenge in uniformity, no need for the Spirit in homogeneity. There is no greaterchallenge, no greater need for the Spirit, than when people who live and look fundamentally different are baptized into one body.

INSPIRED COMPROMISE

Lesson three leads to a small Baptist church, somewhere in Oklahoma, that was happy staying small, Baptist and American. My friend once told me about 50 Ghanaian immigrants who visited them and announced, “We’re Baptists. We want to worship with you.” Imagine that.

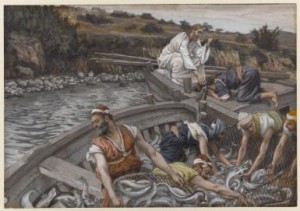

The earliest Jewish church experienced a flood of Gentiles that was a lot like the experience of that small Baptist church. A very Jewish apostle Peter travelled to the home of Cornelius in Caesarea, where he saw the Spirit outpoured on — get this! — Gentiles, while Paul and Barnabas dipped their toes in the Mediterranean and saw Gentiles flock to faith in Jesus.

In the earliest days of the church, just decades after Jesus died, a flood of Gentile believers into a Jewish church changed everything. In “The Open Secret,” Lesslie Newbigin, a 20th-century missionary in India, wrote about this episode: “It is not as though the church opened its gates to admit a new person into its company, and then closed them again, remaining unchanged except for the addition of a name to its roll of members. Mission is not just church extension. It is something more costly and more revolutionary.”

Mission isn’t just church extension. Mission prompts a revolution. And where there’s revolution —transformation — there’s almost always opposition. While some people are lunging ahead, others are digging in their heels. This is the nub of lesson three — and where the Holy Spirit surfaces.

For some early Jewish followers of Jesus who dug in their heels, the change was just too much. They demanded, “Unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moses, you cannot be saved” (Acts 15:1). Peter fired back, “And God, who knows the human heart, testified to [the Gentiles] by giving them the Holy Spirit, just as he did to us; and in cleansing their hearts by faith he has made no distinction between them and us.”

How did the early church find a way out of this? How’d they escape the inevitable — and all too familiar — “I’m right, you’re wrong” prelude to a split?

Well, to be honest, they argued. Fiercely. “And after Paul and Barnabas had no small dissension and debate with [the believers who championed circumcision], Paul and Barnabas and some of the others were appointed to go up to Jerusalem to discuss this question with the apostles and the elders.” The word,dissension (stasis), elsewhere in the book of Acts describes Ephesian riots (19:40) and a rigid division between Pharisees and Sadducees that turned so violent, Roman soldiers had to intervene (23:7, 10). “No small dissension,” which pitted Peter and Paul against the Pharisaic followers of Jesus was not civil debate. It was aggressive, vicious, even violent.

That’s only half the story. This dissension joined with debate (Acts 15:2, 7). This word, debate, tells us that the church was committed, even with explosive arguments, to intelligent investigation. Later in Acts, Roman procurator Festus tells King Agrippa about Paul’s case: “Since I was at a loss about the investigation [zetesis] of these questions, I asked whether he [Paul] wished to go to Jerusalem and be tried there on these charges” (25:20). Debate, zetesis in Greek, is not argument for argument’s sake, but the intense investigation of a particular issue, like the intractable question: Are Gentiles who follow Jesus obligated to observe the commands of Torah?

Where does the Holy Spirit fit into this violent argument? In the path to compromise.

The head honcho in Jerusalem, James, appeals to the Holy Spirit — it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us — when he sends word of a compromise: no circumcision for Gentiles but the need to follow a few Jewish rules nonetheless (Acts 15:28-29).

The decision, James notes, seems good both to the Holy Spirit and to us. The Holy Spirit and us. The Holy Spirit, James claims, is enmeshed in our brutal, bruising path to compromise.

Where does the Holy Spirit fit into all of this? In the tough, gritty work of conflict and compromise. Not in the revelation of a nifty solution. Not by zapping the church with a miraculous absence of malice. Certainly not in schisms and splits.

In this gritty process, we discover a rich vein of the Holy Spirit. Compromise — the battle-scarred road that leads to it, too — can seem good both to the Holy Spirit and to us.

JACK LEVISON is the W.J.A. Power professor of Old Testament interpretation and biblical Hebrew at Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

JACK LEVISON is the W.J.A. Power professor of Old Testament interpretation and biblical Hebrew at Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

ollege. Their schedules are so busy nowadays she has difficulty gathering them for meals. I asked her if she would select a recipe to cook for the Advent Parent Gathering and she chose Taco Soup. We cooked a huge pot of it and served it with bread. We used this simple meal to bring the parents together and practice from the book as if we were one family. We had five tables and each member of the table pretended to be a member of the family (mother, father, child, teen, grandparent, etc). They selected a chapter and practiced sharing the topic with one another while eating their soup and bread. At the end of the gathering, we had our little sales table, with the remaining coloring books, the Feeding Your Family’s Soul book and some other gift items. We sold a lot, especially as it was a perfect time for Christmas gifts! Many parents bought the book for themselves. We also placed a few copies of this book in our parish library so that others who do not want to purchase it may borrow it instead.

ollege. Their schedules are so busy nowadays she has difficulty gathering them for meals. I asked her if she would select a recipe to cook for the Advent Parent Gathering and she chose Taco Soup. We cooked a huge pot of it and served it with bread. We used this simple meal to bring the parents together and practice from the book as if we were one family. We had five tables and each member of the table pretended to be a member of the family (mother, father, child, teen, grandparent, etc). They selected a chapter and practiced sharing the topic with one another while eating their soup and bread. At the end of the gathering, we had our little sales table, with the remaining coloring books, the Feeding Your Family’s Soul book and some other gift items. We sold a lot, especially as it was a perfect time for Christmas gifts! Many parents bought the book for themselves. We also placed a few copies of this book in our parish library so that others who do not want to purchase it may borrow it instead.

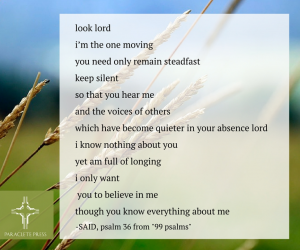

sports cars and younger women. Instead, Cairns realized his spiritual life was advancing at a snail’s pace and time was running out. Midlife crisis for this Baptist turned Eastern Orthodox Christian manifested as a desperate need to seek out prayer.

sports cars and younger women. Instead, Cairns realized his spiritual life was advancing at a snail’s pace and time was running out. Midlife crisis for this Baptist turned Eastern Orthodox Christian manifested as a desperate need to seek out prayer. deeply contented. It surprised me when she admitted that, as a girl, she had been very talented at drawing and drafting and had wanted to be an architect. Instead, she had chosen a life of work in the homes of wealthier people. She never appeared dissatisfied or regretful. She had to work hard, coming to work from the North on the bus in the early morning chill, wrapped in a crocheted shawl, cooking and cleaning before most people had woken up. She was good at her job, proud of her food, loved and respected by the people she worked for, and she always made time to teach me how to make one thing or another. And she shared with me her devotion to Saint Jude Thaddeus, who had helped her when her son’s health was failing.

deeply contented. It surprised me when she admitted that, as a girl, she had been very talented at drawing and drafting and had wanted to be an architect. Instead, she had chosen a life of work in the homes of wealthier people. She never appeared dissatisfied or regretful. She had to work hard, coming to work from the North on the bus in the early morning chill, wrapped in a crocheted shawl, cooking and cleaning before most people had woken up. She was good at her job, proud of her food, loved and respected by the people she worked for, and she always made time to teach me how to make one thing or another. And she shared with me her devotion to Saint Jude Thaddeus, who had helped her when her son’s health was failing.

Out of Zion, the perfection of beauty, God hath shined.

Out of Zion, the perfection of beauty, God hath shined.

d can inspire hope life daffodils dancing after winter. It can be as fragrant as a bunch of lilacs brought home to a crystal vase or as bold as a dandelion pushing its way through a rock. An engaging word feeds like a plump sun-ripened tomato or satisfies like a chunk of summer watermelon.

d can inspire hope life daffodils dancing after winter. It can be as fragrant as a bunch of lilacs brought home to a crystal vase or as bold as a dandelion pushing its way through a rock. An engaging word feeds like a plump sun-ripened tomato or satisfies like a chunk of summer watermelon. The year before men landed on the moon, I learned about the Holy Spirit in a small white church, sandwiched between a TV repair shop and a doughnut store on a busy Long Island thoroughfare. We were a church of immigrants. One day, local barber Xavier Munisteri burst out in the middle of worship in words I couldn’t understand. I figured he was speaking Italian. Turns out, he wasn’t speaking Italian — he was speaking in tongues.

The year before men landed on the moon, I learned about the Holy Spirit in a small white church, sandwiched between a TV repair shop and a doughnut store on a busy Long Island thoroughfare. We were a church of immigrants. One day, local barber Xavier Munisteri burst out in the middle of worship in words I couldn’t understand. I figured he was speaking Italian. Turns out, he wasn’t speaking Italian — he was speaking in tongues. JACK LEVISON is the W.J.A. Power professor of Old Testament interpretation and biblical Hebrew at Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

JACK LEVISON is the W.J.A. Power professor of Old Testament interpretation and biblical Hebrew at Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. We gather under a few stunted trees at the center of the cemetery for the interment of beloved Auntie Cleone, who died at 99, just a few days ago. Even under the trees, I have to shade my eyes against the unrelenting sun to gaze at the short rows of headstones. I’m remembering the way she harvested dozens of peonies still tight in their buds, wrapped each one in wax paper, twisted the top to slow the blossom, and tucked them into Ball jars. Then she stored the captive peonies in the ice box until the night before Memorial Day. I’m picturing the Country Squire loaded for the drive to Silent Land with crates of empty orange juice cans, the released peonies bobbing in five gallon buckets, and sprigs of mock orange, their lavish fragrance permeating the station wagon. Her three children scraped through the sun-baked earth, scooping out holes for the orange juice cans next to the headstones of great aunts and great uncles, grandparents, and the great grandparents who homesteaded the farm. And they carried bouquet after bouquet to these makeshift vases, filling them with scarlet and crimson and cream—and water, precious water, drawn bucketful by bucketful from the well beneath the windmill.

We gather under a few stunted trees at the center of the cemetery for the interment of beloved Auntie Cleone, who died at 99, just a few days ago. Even under the trees, I have to shade my eyes against the unrelenting sun to gaze at the short rows of headstones. I’m remembering the way she harvested dozens of peonies still tight in their buds, wrapped each one in wax paper, twisted the top to slow the blossom, and tucked them into Ball jars. Then she stored the captive peonies in the ice box until the night before Memorial Day. I’m picturing the Country Squire loaded for the drive to Silent Land with crates of empty orange juice cans, the released peonies bobbing in five gallon buckets, and sprigs of mock orange, their lavish fragrance permeating the station wagon. Her three children scraped through the sun-baked earth, scooping out holes for the orange juice cans next to the headstones of great aunts and great uncles, grandparents, and the great grandparents who homesteaded the farm. And they carried bouquet after bouquet to these makeshift vases, filling them with scarlet and crimson and cream—and water, precious water, drawn bucketful by bucketful from the well beneath the windmill.

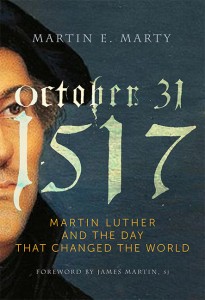

The date that entitles this brief quincentennial prologue may not be immediately recognizable, but it was momentous. On it, Martin Luther posted 95 theses about Christian faith on the door of a church in Wittenberg, Saxony, and launched the Protestant Reformation. While directly prompted by the selling of indulgences, whereby the buyer reduced suffering for sins, the document was fundamentally about salvation through Christ. Luther asserted that salvation was effected by God’s grace alone, approached by faith alone. Faith was manifested by repentance: “the whole life of believers should be penitence,” says the first thesis. Marty, the dean of American Lutheran church historians, argues that, eventually, Luther’s stance, from the beginning acknowledged by the Catholic Church as essentially correct (disagreement’s in the details), became the means of reunifying Christianity through ecumenism, a movement that became explicit and official with the Second Vatican Council of 1962–65. This volume is small but weighty and a solid addition for all modern Christianity collections.

The date that entitles this brief quincentennial prologue may not be immediately recognizable, but it was momentous. On it, Martin Luther posted 95 theses about Christian faith on the door of a church in Wittenberg, Saxony, and launched the Protestant Reformation. While directly prompted by the selling of indulgences, whereby the buyer reduced suffering for sins, the document was fundamentally about salvation through Christ. Luther asserted that salvation was effected by God’s grace alone, approached by faith alone. Faith was manifested by repentance: “the whole life of believers should be penitence,” says the first thesis. Marty, the dean of American Lutheran church historians, argues that, eventually, Luther’s stance, from the beginning acknowledged by the Catholic Church as essentially correct (disagreement’s in the details), became the means of reunifying Christianity through ecumenism, a movement that became explicit and official with the Second Vatican Council of 1962–65. This volume is small but weighty and a solid addition for all modern Christianity collections.