Mark S. Burrows

It is a strange and lovely word, ”longing,” one hard to say quickly because of the arc of the soft “o” followed by the gentle “ng” sound—doubled in this word—which we must give shape to in the back roof of the mouth. Its physiological origin, within the range of our speech, makes it one of the deepest-back and innermost sounds we produce. How fitting for this word, of all words! Its sound reflects the experience it suggests, for it takes time to say it and is delicious in the saying: “longing.” Even as you read these lines, you sense the quiet wandering the word stirs within your heart.

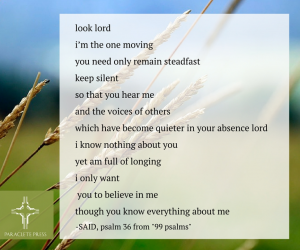

“Longing” describes the spiritual texture of many of the poems found in SAID’s collection, 99 Psalms. Reflecting the experience the word speaks of, his poems approach this theme in ways that startle us, sometimes bending our expectations back on themselves, sometimes puzzling us deeply enough to draw us into new comprehensions, always calling us to look at our own lives more carefully, more honestly, and above all more generously. Consider this one:

Strange to imagine telling God to “keep silent” in order to hear us. Peculiar to suggest that our voices, or the voices of others, become “quieter” in God’s absence. But such sentiments are close to our experience, wondering as we sometimes do if God is attending to us, notices our needs and those of others in the pain, the worry, the confusions that bind us. And, in our wondering, we often fall silent in our pondering, whether in doubt or in hope.

Perhaps, as SAID seems to be suggesting, our longing itself is a kind of belief, one that takes us further—or deeper—than mere knowing. Perhaps our longings are the truest way in which we seek communion with the “other” we sometimes name “God.” Perhaps longing itself is the surest way we learn to believe, especially when our lives are abruptly interrupted, our hopes shattered, our confidence chilled. For longing, more than knowing, is what guides us in the ways we seek the God who is “steadfast” in the midst of our commotions and confusions.

As the poem reaches its final pause, what a marvelous moment of courage we find: namely, the chutzpa involved in asking the Lord, who “know[s] everything about [us],” to believe—in us. But what else is this than mercy? The poem unsettles the thin conventions of our piety, and yet insists on speaking to a place deep in our soul—where our heart longs for the God whom, we pray, will still turn to us even though knowing everything about us, with the shadows and debris alongside the bursts of clarity and moments of goodness that mark our lives.

We often speak about God as “word” and imagine the Lord as One who is still speaking with us, but we know what it means to face the long silences when this does not seem so. In such times, longing can be our guide as we desire communion with One who is silent and steadfast enough to give us room to be, space to grow, time to listen. Our longings are not the goal, but in this long journey of faith, they are often the way.

Mark Burrows is a poet, theologian, and teacher. He currently serves as professor of theology and literature at the Protestant University of Applied Sciences in Bochum, Germany. His recent publications in English include an essay in the forthcoming issue of Weavings, “Listening into the Heart’s Silences” (Vol. 31.3), and, as editor, Breaking the Silences. Poetry and the Kenotic Word (Peter Lang, 2015). His translation of Rilke’s Book of Hours, entitled Prayers of a Young Poet, was just published in a newly revised paperback version (Paraclete, 2015), and his translation of SAID’s 99 psalms is also available as a volume of Paraclete Poetry (2013).