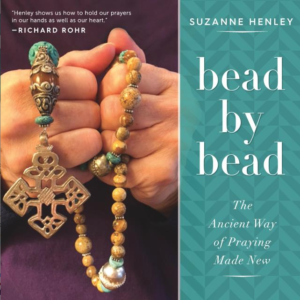

Read and enjoy this excerpt from Suzanne Henley’s Bead by Bead: The Ancient Way of Praying Made New in honor of Saint Teresa of Calcutta’s birthday (August 26th).

Chapter 4:

Clearing Your Cache and Beginning to Pray

Regardless of how many years and how earnestly you have prayed, author John McQuiston reminds us, “Always We Begin Again.” Each attempt at prayer is a new one. There are no referees, no winning score, no out-of-bounds, no penalties. You must bring your whole self to it. Several years ago I heard Richard Rohr say, “I have prayed for years for one good humiliation a day, and then, I must watch my reaction to it. I have no other way of spotting both my denied shadow self and my idealized persona.” Prayer can be messy. It is not—and should not be, I believe—a tidy package. We must wade through the mud first. As Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh reminds us, “no mud, no lotus.”

Jesus tells us in Matthew 6:5–6 to go into our closet to pray. Closets are of course our first choice as children when playing Hide and Seek, and that often describes prayer: Hide and Seek. And we are still children. However, I retreat at the image of the Holy Spirit in my closet—ancient dust balls roiling among the cluttered clogs and worn-out sandals, pants legs slapping about, a sweater or two slumped off hangers—and the two of us hunkering knee to knee amid the musty odor of tee shirts and jeans whining, “Put me in the laundry!” This closet with its housekeeping embarrassments of course is the untidy closet of my heart. And, as messy as it might be, this is exactly where we all must begin. One of the main points of prayer, it seems to me, is in fact to air our dirty laundry.

We can spend a lot of time and effort hiding from what we know to face in prayer—“That of which we are not aware, owns us,” James Hollis reminds us in Finding Meaning in the Second Half of Life—but sometimes roles switch; the Spirit sometimes seems to hide, sometimes for months, even for years.

In 1989 Mother Teresa came to Memphis to speak. Two of my children were quite young and could have no idea at the time of the enormity of devotion and accomplishment of this tiny woman, but I wanted them to have a memory of her presence. For some lucky reason we were given aisle seats. We waited a long, very fidgety time. Suddenly there was a stir. Mother Teresa did not come out on a stage two hundred feet away but was actually walking up the aisle toward us. The packed coliseum was quiet with respect and awe as she approached. Then she was beside us, and my son Walker, in the carrying voice of an excited child, stood up and exclaimed to the hushed auditorium, “Look, Mom, she has on sandals! And they’re just like mine!”

We now know that Mother Teresa, as many of us do, experienced her own very dark night of the soul. According to her letters—which she never believed would be made public—the desolation and abandonment by God she felt lasted for fifty years, beginning almost from the moment she arrived in Calcutta to begin the work she believed Jesus had commanded her to do. Continuing her work, and always smiling (“a mask,” she called it), she wrote of the “torture,” “emptiness,” and “darkness” she lived with for the majority of her life. For a period she even stopped praying. We balk and flounder, searching for an adequate explanation for this gut-wrenching information—or dismiss it with a shrug of psychological shoulders. As unutterably painful as those years must have been for her, though, they tell each of us in our own dark nights of searing doubt and unbearable loneliness that we’re in good company. We all wear the same sandals.