On Friday, February 18th we celebrate the 461st anniversary of the death of Martin Luther, that great theologian and reformer of the Church. We know so much about the bold deeds and writings of this man and his many contemporaries who changed the world, that they have become almost legendary for us. But thankfully, we also know them just as men – people, sinners saved by grace like you and I – who clung to a relationship with God the Father and Christ their Savior, wrestling with their faith, and fervent in their prayer. On this anniversary of Luther’s death, and indeed throughout this important anniversary year of the Reformation, let us join Luther – not as Reformers, or theologians, but simply as men and women seeking to know more about God, and more about ourselves, through prayer. Paraclete offers this new book, Prayers of the Reformers, as a help and guide. And as Luther himself is credited with saying, “Grant that I may not pray alone with the mouth; help me that I may pray from the depths of my heart.”

From the Introduction

Some historical events have such a profound impact and such a multitude of consequences that the world is changed forever in their wake. The Protestant Reformation must certainly be counted among such events. Given the loud repercussions—social, theological, cultural, liturgical (among so many others)—that have continued to echo through the centuries, even to our own day, it might be easy to forget that behind the forces that brought about such change were devout people of faith, whose everyday lives were marked by times of prayer. The Protestant “reformers,” as they have come to be known, were also, and perhaps most importantly, “pray-ers.”

Some historical events have such a profound impact and such a multitude of consequences that the world is changed forever in their wake. The Protestant Reformation must certainly be counted among such events. Given the loud repercussions—social, theological, cultural, liturgical (among so many others)—that have continued to echo through the centuries, even to our own day, it might be easy to forget that behind the forces that brought about such change were devout people of faith, whose everyday lives were marked by times of prayer. The Protestant “reformers,” as they have come to be known, were also, and perhaps most importantly, “pray-ers.”

Certainly we learn much from the writings they have left, as well as the many records of their lives. But they have also left us their prayers, like windows into their own souls, and in their prayers we can meet them and learn from them. The prayers of the Protestant Reformers are filled with some of the central themes of their faith, perhaps first among them being an unshakable confidence in God’s supreme authority over all time and space. History is God’s workplace.

He does not stand afar off, but actively and intimately participates in the lives of people in order to show his love and bring about his will. Many of the Reformers’ prayers reflect this conviction as, again and again, they seek for God’s will to be done on earth, and in themselves. Asking for the grace to be obedient to God is not so much an expression of servility as it is an expression of hope—the hope that my ordinary life can play a part in God’s extraordinary plan. The Reformers were convinced that we are all God’s instruments for the working of his purposes, and so we pray for what we need in order to serve him faithfully.

A second recurring theme follows directly: utter dependence on God for everything needed to live for God. Here are prayers for wisdom, guidance, perseverance, protection, and for daily bread in all its forms, offered in the certainty that God alone is the source of such gifts. Turning to God with confidence starts by acknowledging one’s own weakness and helplessness, beginning with the confession of one’s own sin. Our dependence on God is never more profoundly apparent than when we stand (or fall) in need of his grace, mercy, and forgiveness, all of which are generously given through the shed blood of his only Son. For the Reformers, every prayer we offer is built upon the foundation of Christ’s saving Cross and Resurrection.

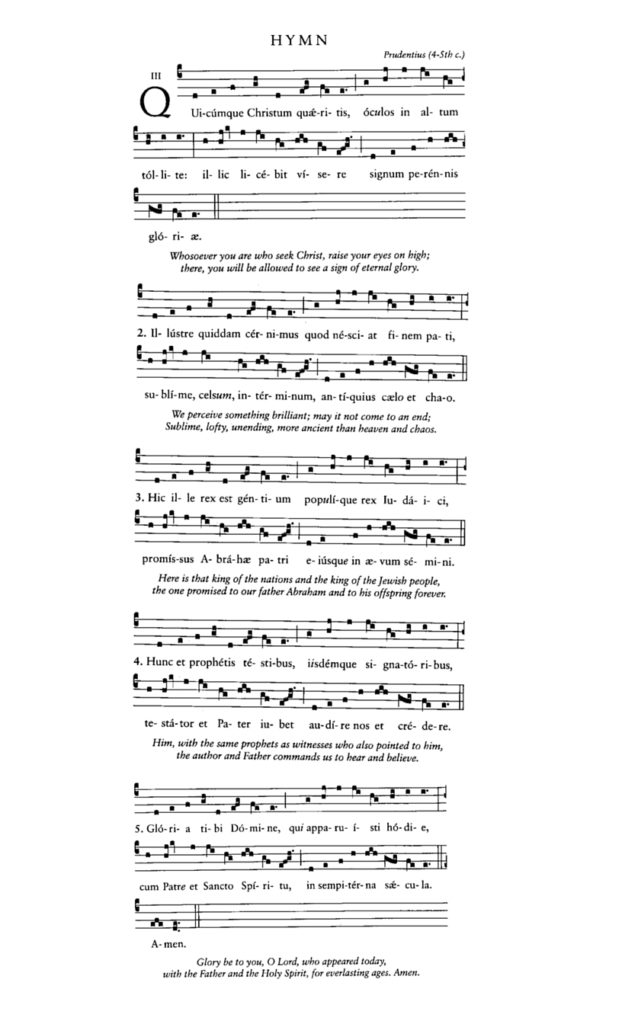

Third, implicitly and sometimes explicitly, these prayers express our need for illumination by the Holy Spirit and the Word of God. In the writings of the Reformers there often appears an almost seamless movement between quotations from the Bible and phrases of prayer. As students of God’s word, they conversed with God using his own “language.” They believed that one must pray in order to understand the Scriptures, and that one must read the Scriptures in order to know how to pray. And, in both cases—when reading the Bible and when praying—they taught that we depend upon the Holy Spirit to shed God’s light upon minds and hearts that would otherwise be left blind to God’s handiwork. Praying for light is as important as praying for bread, for the Christian cannot live without either.

Fourth, trust in God stands as the chief motivator for prayer. Just as he is all-powerful, God is also all-loving. We express our needs and desires, sometimes cheerfully and sometimes despairingly, but always believing that God’s answers will spring from an eternal love that is as unchangeable as it is mysterious. We ask of God because we trust in God, that he is faithful to his promises, that he is always ready to hear and to answer, and that he never will turn away when we call out to him. All of the Reformers expressed this kind of trust through their prayers, and some of them showed it even in the moment of their violent deaths.

Finally, for the Reformers, the ultimate goal of praying was the same as it was for living—that God may be glorified.

Thanksgiving for God’s goodness is directed to the same end as asking for God’s forgiveness. In both cases, and in every case between, God’s answer will elicit praise from our hearts as well as from our lips. If our aim is to live “to the praise of his glory,” then woven through all of our prayers is the ultimate hope that, in Christ, God will unite all things in heaven and on earth, including us, into his everlasting kingdom. So we pray in order that his kingdom may come now, in whatever way it can, and that we will always be part of that coming.

ollege. Their schedules are so busy nowadays she has difficulty gathering them for meals. I asked her if she would select a recipe to cook for the Advent Parent Gathering and she chose Taco Soup. We cooked a huge pot of it and served it with bread. We used this simple meal to bring the parents together and practice from the book as if we were one family. We had five tables and each member of the table pretended to be a member of the family (mother, father, child, teen, grandparent, etc). They selected a chapter and practiced sharing the topic with one another while eating their soup and bread. At the end of the gathering, we had our little sales table, with the remaining coloring books, the Feeding Your Family’s Soul book and some other gift items. We sold a lot, especially as it was a perfect time for Christmas gifts! Many parents bought the book for themselves. We also placed a few copies of this book in our parish library so that others who do not want to purchase it may borrow it instead.

ollege. Their schedules are so busy nowadays she has difficulty gathering them for meals. I asked her if she would select a recipe to cook for the Advent Parent Gathering and she chose Taco Soup. We cooked a huge pot of it and served it with bread. We used this simple meal to bring the parents together and practice from the book as if we were one family. We had five tables and each member of the table pretended to be a member of the family (mother, father, child, teen, grandparent, etc). They selected a chapter and practiced sharing the topic with one another while eating their soup and bread. At the end of the gathering, we had our little sales table, with the remaining coloring books, the Feeding Your Family’s Soul book and some other gift items. We sold a lot, especially as it was a perfect time for Christmas gifts! Many parents bought the book for themselves. We also placed a few copies of this book in our parish library so that others who do not want to purchase it may borrow it instead.